Selected Essays and Reviews

|

"My Platonic Romance on the Psych Ward" (The New York Times; read by Miriam Shor on the Modern Love podcast)

Anita and I met five years ago as roommates at a hospital just outside of New York City. According to the brochure in our patient intake folders, the hospital’s scenic grounds boasted rolling lawns, open meadows, forests and a gazebo. But why would we care about the landscaping? The brochure reminded me of a commercial I had seen for Hulu while watching Hulu. We didn’t need an advertisement for the hospital. We were locked inside. |

|

"What's in a Necronym?" (The Believer; reprinted in Spanish in El Malpensante; reprinted in Italian in Black Coffee; named a Notable Essay in Best American Essays; featured by Longreads)

I am named after the daughter my father lost. I remember the day I first learned about her. I was eight. My father was in his chair, holding a small white box. As my mother explained that he had a dead daughter named Jeanne, pronounced the same as my name, “without an i,” he opened the box and looked away. Inside was a medal Jeanne had received from a church “for being a good person,” my mother said. My father said nothing. I said nothing. I stared at the medal. |

|

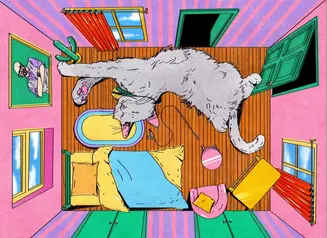

"The Truth About Cats and Daughters" (The New York Times Magazine, a NYT Editors' Pick)

My mom talks about her cat the way I talk about my mom: “She turns on me on a dime,” she’d say. Or, “Even if she had the whole house to herself, she wouldn’t be happy.” Or: “There’s something wrong with her. She can’t help it. It’s probably chemical.” One day, my mom described a situation with her cat, Brooklyn, using language she’s probably used to summarize her dynamic with me: “I’m not talking to her. She knows I’m mad.” |

|

"Absent Things As If They Are Present" (The Believer; reprinted in French in Editions Inculte; anthologized in Read Harder; featured by Longform)

“We say that an author is original when we cannot trace the hidden transformation that others underwent in his mind,” Valéry wrote. “What a man does either repeats or refutes what someone else has done—repeats it in other tones, refines or amplifies or simplifies it.” But instead of concealing or denying their influences, erasurists acknowledge that they have come from somewhere, not nowhere, and make clear the chaotic process of creating art. |

|

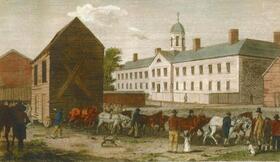

"Location, Location, Location: A Brief Personal History of House-Moving" (The Believer online; featured by Longform and Longreads)

In the days of candles and outhouses, Americans lifted and moved countless houses. To raze an old house and build a new one proved more costly and difficult than laying it on logs and pulling it through unpaved streets by horse or oxen. A 1799 engraving by William Birch and Son reveals a team of horses pulling a saltbox structure attached to wooden wheels through Philadelphia’s Walnut Street. Since then, Americans have moved lighthouses, churches, hotels, theaters, even an airport terminal. |

|

"Dream a Little Dream of Me" (The Believer online)

“California Dreamin’” by the Mamas and the Papas returns me to my hometown amusement park, with its roller coasters, buttery elephant ears, and the grassy knoll where I smelled pot for the first time while reading Tolstoy for the first time. Twenty years ago, a season pass cost only $85, and I lived a ten-minute drive away. Sixteen and immersed in War and Peace, I considered the amusement park a perfectly good place to read. As an introvert, I enjoyed being surrounded by strangers who expected nothing of me. |

|

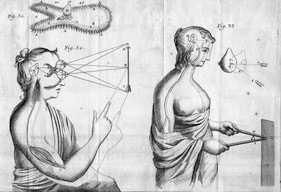

"The Glass Eye: Seeing and Artificial Eyes" (The Believer online; featured by Longform)

I had been carrying my father’s glasses with me. He was in his casket, looking like no one I knew. I slid them on his face. “That looks more like him,” my mother said. But that’s not what I wanted. I wanted him to see me. |

|

"Columbo's Eye: An Investigation of Grief" (Powell's)

When I was four, doctors removed my dad’s left eye because of a rare disease. I remember, and my mom remembers, my relentless questioning: What will happen to the eye? What does the world look like with one eye? Is it like when you close one eye? Does half of what’s in front of you disappear? Will the other eye be okay? Will the other eye have to work harder? Will it get tired? “Columbo has a glass eye,” my mom told me. And that shushed me — because if Columbo, a disheveled, chain-smoking, blue-collar L.A. homicide cop, could solve crimes with one eye, my dad would be okay. |

|

"Walter Potter's The Death and Burial of Cock Robin" (The Believer)

Potter's work gains depth by casting dead animals as civilized humans: a frog shaves another frog, two guinea pigs play cricket, seventeen ginger tabby and white kittens partake in colorful pastries at a tea party. So it is in The Death and Burial of Cock Robin: Avian mourners perch on a leafless tree while others line up in pairs behind the coffin, heads lowered; several shed glass tears. |

|

"Death and Child's Play" (The Believer)

Children dream up new uses for toys every day—a yo-yo that hypnotizes dogs! an Easy-Bake oven that tans or melts Barbie dolls!—but Frances Glessner Lee, millionaire heiress to a farm-implement fortune, was fifty-two when she began transforming dollhouses into tools for serious forensics. Her Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, a series of murder-scene dollhouse dioramas intended to train budding gumshoes in the 1930s and ’40s, asks aspiring detectives to think like children: to forget that the dolls are dolls and plunge into macabre games of make-believe based on real stories of, typically, suicide or murder. |

|

"Emily's Lists" (Times Literary Supplement)

At least four Broadway-produced plays, five novels, 186 published poems, two children’s books, and a Simon and Garfunkel song (“For Emily, Wherever I May Find Her”) are about Emily Dickinson, usually portraying her as a spinster, a madwoman, a helpless agoraphobic, always in white, hiding away in the upper rooms of her New England home, shunning publication as she did society. |